The world is filled with cycles.

Each day is a cycle, with morning, midday, evening, and night each having their own peculiar character. Six days of labor precede the day of rest before repeating itself again. Spring blossoms into Summer, which eases into Fall, descends into Winter, and is reborn again as Spring. Even the history of polities and cultures appear to follow cycles. There was a reason, after all, that our Classical forebears viewed history as fundamentally cyclical—unending, bounded, and fatalistic.

The Medievals did not share that fatalism, in large part because of the widespread acceptance of Christianity. To the Medieval mind, though history has its seasons, these cycles are working toward the final end described in Revelation 21—the true Happily Ever After where every tear is wiped away and God dwells with his people forever.

On the other hand, the Faustian spirit of our age rebels at the notion that we might be constrained by the cycles of the world. Perhaps the greatest indication that the Faustian age is at an end is that thinkers are returning to the idea of cycles with lengths that are comparable to human lifetimes—or longer. Consider the following:

In The Fourth Turning, Strauss and Howe describe how American (and Western) political life is characterized by a repeating succession of four phases, the High, the Awakening, the Unraveling, and the Crisis. The total time for these four phases is roughly eighty years. Their observations align with the crises that defined American history: the Revolution, the War Between the States, the World Wars, and the current crisis. But this cycle can be traced back as far back as the Baron’s Revolt of AD 1215.

In addition to the eighty-year cycle, there is has been a major financial crisis, followed closely by a major political realignment, every fifty years. This cycle occurs in democratic societies that outsource their fiscal policy to a central bank. America’s current crisis promises to be especially interesting because, this time, the eighty-year crisis and the fifty-year crisis will occur simultaneously.

So we’re starting to come to grips with the fact that there are at least two kinds of cycles that are significantly longer than the ones with which we are most familiar. But what if I told you that the history of Western Civilization has been shaped by an even longer cycle—a cycle so long that many human lifetimes pass in the course of its completion?

This cycle is so long that it has only occurred three times since the Neolithic Age—and only the latest one happened during recorded history—but each times it happens, the results are of cataclysmic proportions, drastically changing the course of history for all time.

I am referring to the Migration Cycle1.

The Migration Cycle is exactly what its name implies: a cycle characterized by seasons where the movement of peoples builds up, reaches a peak, and then tapers off as the migrating peoples settle down to build new civilizations atop the ones they destroyed—or are driven off by the peoples they intended to displace. The peak time of the Migration Cycle, which I call the Deluge, is characterized by mass migration, political instability, war, plague, famine, and a general retraction of civilization and civilizational progress as people forsake more “elevated” pursuits in order to prioritize survival. Technological progress stalls and knowledge is often lost. But what remains at the end of the Deluge is able to blossom once again into high culture in the ensuing centuries. After enough time has passed, however, the peoples who survived the Deluge stagnate and once again become vulnerable to mass migration.

Since no discussion on such a cycle can be done without looking at the events themselves, I will examine the peaks in the Migration Cycle concerning which we have some information. We will begin with the most recent iteration of the Deluge:

The Barbarian Invasions (ca. AD 400-600)

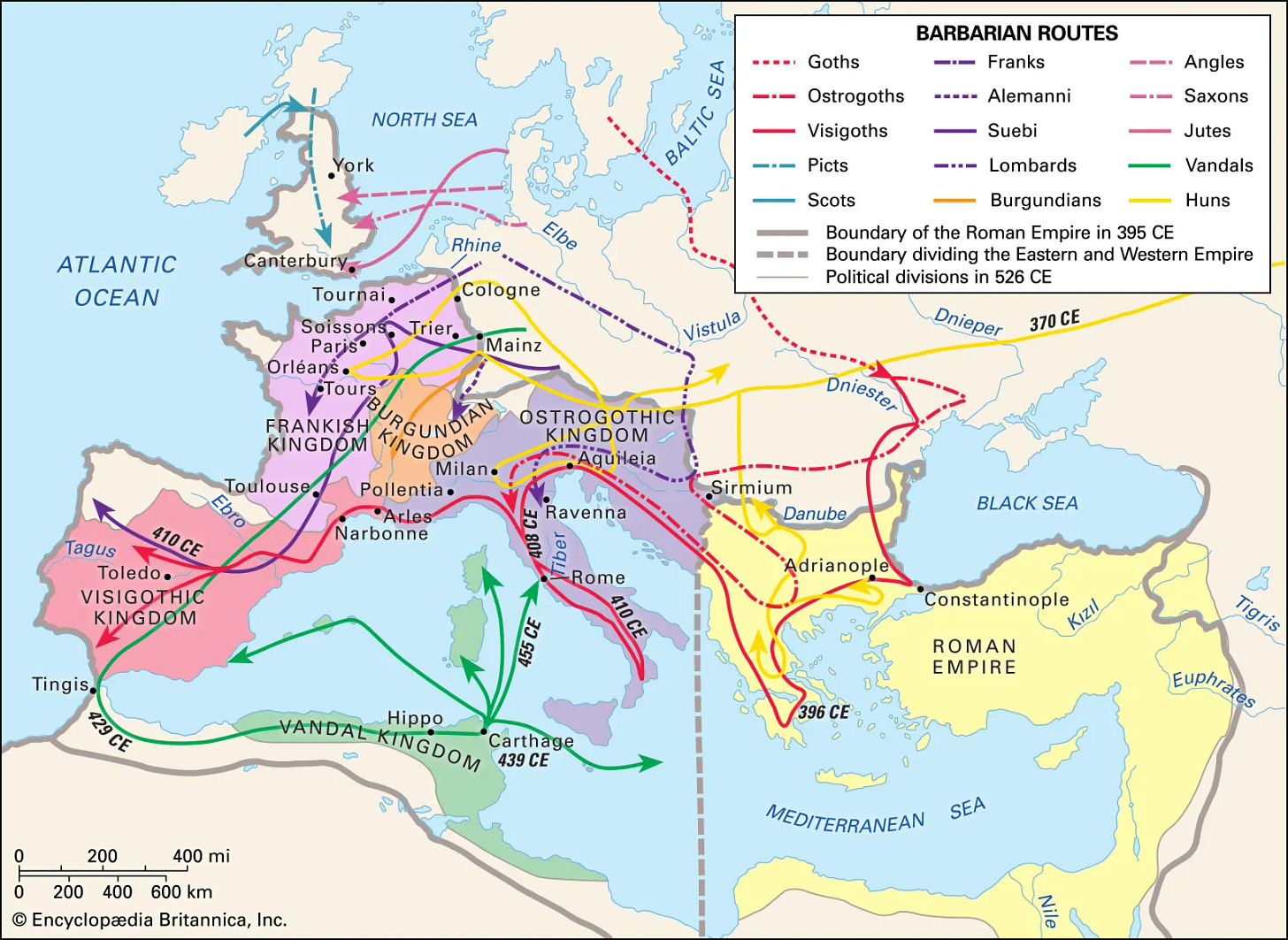

The Barbarian Invasions, also called the Migration Period, refers to the massive influx of Germanic tribes across the borders of the Roman Empire beginning around AD 400. We know the names of the invaders: Angles, Franks, Gaels, Jutes, Ostrogoths, Vandals, Visigoths, and most importantly the Huns. It was the Huns who emerged from the steppe, conquering, raping, and pillaging those unfortunate enough to meet them. Before their wrath the other peoples fled, and so the Huns acted like a bulldozer, driving these people en masse into Roman territory.

If these people had been driven into Roman territory four hundred years earlier, our history would be built atop their bones. But the Romans that lived in AD 400 were not the same Romans that had mastered the Mediterranean. Accustomed to Empire, dependent upon state welfare programs like the Grain Dole, denuded by endless bread and circuses, and taxed into oblivion to fund elite vanity-projects, these Romans were unsuited to the task of defending their land against foreign incursion. Additionally, several of the invading tribes had served as auxiliaries in the Roman legions in centuries past, giving them time to acclimate to Roman battlefield technology and tactics.

In short, the Empire’s greatest strength in 100 BC had by AD 400 become its greatest weakness: it was populated by Romans.

Rome has left us with many magnificent ruins, thinkers, and institutions, and because of this it’s easy to romanticize her and miss just how stagnant Rome had become at this time in its history. But it is essential for us to do so; the stagnation of this once-great people was the most direct cause for the barbarian invasions in the first place.

Rome’s stagnation was inadvertently summarized by Sextus Julius Frontinius, a distinguished Roman engineer who lived from AD 40-103: “Inventions have long since reached their limit, and I see no hope for further developments.” Frontinius’ prognosis is understandable, given his vantage point in history: at this time, the last major scientific development of Classical antiquity would occur less than fifty years after his death; the Ptolemaic model of the solar system would be developed by Ptolemy in AD 1502, but after this there is a dearth of scientific developments in Western Europe until the eleventh century.

The stagnation of Rome is further described in The Triumph of Christianity by Rodney Stark:

Like all ancient empires, Rome suffered from chronic power struggles among the ruling elite, but aside from that and chronic border wars and some impressive public works projects, very little happened—change, whether technological or cultural, was so slow as to nearly go unnoticed.

— Stark, ch. 14, p.239

This stagnation was emblematic of a rot that permeated every aspect of Roman society. Gradually, over centuries, the people of Rome had lost the ability to respond effectively to new challenges. The result was technological and cultural stagnation, collapsing birthrates, lagging production, and poor tax revenues. The most obvious cause of all this was the communist-style rule of Rome’s patricians, who taxed their people down to bare-subsistence level:

Even most free Romans lived at a bare subsistence level, not because they lacked potential…but because a predatory ruling elite extracted every ounce of “surplus” production. If all production above bare minimum needed for survival is seized by the elite, there is no motivation for anyone to produce any more. Consequently, despite the fabulous wealth of the elite, Rome was very poor. As E.L. Jones noted, “emperors amassed vast wealth but received incomes that were nevertheless small relative to the immensity of the territories and populations governed.”

—Ibid

Imagine, then, what happened to the provinces overrun by the “barbarians.” Suddenly, newcomer and resident alike were no longer connected to the vast wealth-extraction system based in Italy. Their government suddenly became much more local, and taxes were used to develop local resources and infrastructure.

That isn’t to say that this migration happened all at once. The Cambridge Medieval History discusses how the migration of Germanic tribes into the Roman interior accelerated over time:

The pressure of the population of the German forests upon the Roman world was so ancient and inveterate, and so much of that population had in one way or another entered the Empire for so long a period, that when the barrier finally broke, the flood came as no cataclysm, but as something which was almost in the natural order of things. There may have been movements in Central Asia which explain the final breach of the Roman barriers; but even without invoking the Huns to our aid, we can see that at the beginning of the fifth century the Germans would finally have passed the limes, and the Romans at last have failed to stem their advance, owing to the simple operation of causes which had long been at work on either side.

So immigration into the Empire was occurring in the centuries prior to the Barbarian Invasions; the Invasions are famous, then, for being the time at which immigration reached a fever-pitch and irrevocably altered the social fabric of the region.

Neither is it appropriate to think that Romans were “liberated” by the barbarian tribes. The incoming tribes brought with them fire, plunder, and slaughter—both alike for the lands they won and failed to win. The native Roman peoples were forced to make accommodations to the invaders at their own expense. From the same section of the Cambridge Medieval History:

Germanic tribes, with their kings and their dooms, their moots and their fyrds, settle bodily on the soil, as new forces in the domain of politics and economics, of religion and of law. The Latinised provincial pays a new allegiance to the tribal king: the Roman possessor has to admit the tribesmen as his "guests" on part of his lands; the Catholic priest is forced to reconcile himself to the Arianism, which these tribes had inherited from the days of Ulfila; and the Roman jurist, if he can still occupy himself by reducing the Codex Theodosianus into a Breviarium Alaricianum, must also admit the entrance of strange Leges Barbarorum into the field of jurisprudence.

But the destruction of the wealth-extraction system of the Roman ruling class combined with the localization of power structures allowed for the deliverance of Western Europe from a Roman rulership that had become a choking cultural miasma.

The results were nothing short of explosive. Rodney Stark explains further:

…many new technologies began to appear and were rapidly and widely adopted with the result that ordinary people were able to live far better, and, after centuries of decline under Rome, the population began to grow again. No longer were the productive classes bled to sustain the astonishing excesses of the Roman elite…. Instead human effort and ingenuity turned to better ways to farm, to sail, to transport goods, to conduct business, to build churches, to make war, to educate, and even to play music.

—Stark, ch. 14, p.240

Stark goes on to lampoon the notion of the existence of the “Dark Ages”3:

In any event, there was no “fall” into “Dark Ages.” Instead, once freed of the bondage of Rome, Europe separated into hundreds of independent “statelets.” In many of these societies progress and increased production became profitable, and that ushered in “one of the great innovative eras of mankind,” as technology was developed and put into use “on a scale no civilization had previously known.” In fact, it was during the “Dark Ages” that Europe took the great technological and innovative leap forward that put it ahead of the rest of the world.

—Ibid

The following technological and social developments occurred during the time period between AD 600 and AD 1000, which is the start of the High Middle Ages.

Water-powered mills and dams allow the mechanization of processes like bread-baking and textile manufacturing.

Windmills are used to reclaim land formerly swallowed by the ocean. Much of Belgium and the Netherlands was created by this process.

Farms were rotated in and out of production to allow the land to rest. This massively increased food production.

Chimneys were developed, which significantly reduced the likelihood of city fires.

The slave trade was outlawed in Francia due to the efforts of Queen Bathilda in the late seventh century. She was later canonized as a saint.

Musical notation was developed, along with polyphonic music.

There are other advancements in science, the arts, architecture, warfare, and business that are significant in their own right, but the developements listed stand apart for two reasons. First, they are foundational to many of the advancements that emerge later. Second, many of these developments occur extremely quickly after the conclusion of the Invasions; several of these advances were made in the seventh century, even as “aftershock” migrations (like those of the Norse, Magyar, and Arab peoples) continued until AD 1100.

Some technologies were lost, however. The Roman recipe for concrete is famous for producing structures that are still standing to this day. It wasn’t until recently that the secret to their mansonry’s longevity was understood. Their hypocaust heating systems were unreplicated for centuries afterward. But these technologies, while interesting in their own right, did not present a block to the wider technological development that occurred after the Barbarian Invasions.

Perhaps the greatest loss is that of ancient writings that informed the discourse of thinkers, governors, and generals during that time. Our library of classical literature, while rich and varied, is still a pale shadow of its former Classical glory. Yet we can be grateful that so much of the most important works from that time period survive4.

The survival of those manuscripts must be credited to two things: the system of monasteries developed in the Western Empire in the centuries leading up to the Barbarian Invasions, and the survival of Classical civilization in Eastern Rome. The Byzantines, while beset on all sides during this time, were able to keep their state, their people, and their civilization intact. This was a centuries-long endeavor with many ups and downs, and there were times when the Eastern Emperor was reduced to a puppet (e.g. by the Goths) or a tributary (e.g. by the Huns). But Providence gave them the right men at the right time to take back their nation. Thanks to the survival of the East, much knowledge was saved that would go on to profoundly influence the West.

While modern civilization owes its existence to the fall of Rome and the extinction of Classical civilization, Classical civilization in turn owed its existence to the extinction of a prior set of cultures. We thus turn to the next iteration of the Migration Cycle: the mysterious Bronze Age Collapse. This will be the subject of the next installment.

So far as I’ve been able to find, no one else has identified this cycle. Therefore, all the terminology around this concept is my own. If someone has beaten me to the punch, let me know and I will give proper credit.

It is ironic that this model would turn out to be incorrect, especially since a heliocentric model had been proposed by Aristarchus of Samos in the 3rd century BC. To be fair to Ptolemy, however, the geocentric model with epicycles proved effective at predicting the locations of the planets, and it would require state-of-the-art observational equipment that wouldn’t be available until the 16th century for a geocentric model to surpass the Ptolemaic in predictive power.

Many medieval historians vehemently reject the notion of a Dark Age because in the last couple centuries, the concept has been hijacked by second-rate historians with an axe to grind. The result is that the term has gained a common everyday meaning that has no connection to the realities of the period to which it refers. Yet future installments of this series will show that the concept does have some merit, and an appropriate change in terminology will more effectively capture the dynamics of the “Dark Age” period.

And as much as I may be tempted to curse the Mohammedans for their burning of the Great Library, it may also be the case that some knowledge contained within that library needed to be destroyed. There are some kinds of knowledge that corrode the soul of the knower.